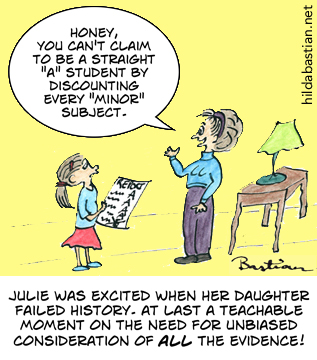

Straight ‘A’ student

Cherry picking results can be misleading.

Key Concepts addressed:- 2-6 Peoples' outcomes should be assessed similarly

- 2-7 All should be followed up

- 2-11 All fair comparisons and outcomes should be reported

- 2-8 Consider all of the relevant fair comparisons

Details

Unfortunately, little Suzy isn’t the only one falling for the temptation to dismiss or explain away inconvenient performance data. Healthcare is riddled with this, as people pick and choose studies that are easy to find or that prove their points.

In fact, most reviews of healthcare evidence don’t go through the painstaking processesneeded to systematically minimize bias and show a fair picture. You can read more about how it’s done thoroughly in this explanation of systematic reviews at PubMed Health.

A fully systematic review very specifically lays out a question and how it’s going to be answered. Then the researchers stick to that study plan, no matter how welcome or unwelcome the results. They go to great lengths to find the studies that have looked at their question, and they analyze the quality and meaning of what they find.

The researchers might do a meta-analysis – a statistical technique to combine the results of studies (explained here at Statistically Funny). But you can have a systematic review without a meta-analysis – and you can do a meta-analysis of a group of studies without doing a systematic review.

To help make it easier for people to sift out the fully systematic from the less thorough reviews, a group of us, led by Elaine Beller, have just published guidelines for abstracts of systematic reviews. It’s part of the PRISMA Statement initiative to improve reporting of systematic reviews.

A quick way to find systematic reviews is the National Library of Medicine’s PubMed Health. It’s a one-stop shop of systematic reviews, information based on systematic reviews and key resources to help you understand clinical effectiveness research. You can read more about PubMed Health here.

Do systematic reviews entirely solve the problem Julie saw with those school grades? Unfortunately, not always. Many trials aren’t even published at all, and no amount of searching or digging can get to them. This happens even when the trial has good news, but it happens more often with disappointing results. The “fails” can be very well-hidden. Yes, it’s as bad as it sounds: Ben Goldacre explains the problem and its consequences here.

You can help by signing up to the All Trials campaign – please do, and encourage everyone you know to do it too. Healthcare interventions simply won’t all be able to have reliable report cards until the trials are not just done, but easy to get at.

Text reproduced from http://statistically-funny.blogspot.co.uk/ . Cartoons are available for use, with credit to Hilda Bastian.